[DA-022] GIS&T in Humanitarian Mapping

Humanitarian mapping has become a growing field since its initial success during the Haiti Earthquake in 2010. The emergence of Web 2.0 and the geospatial Web allowed nonprofessionals to contribute to platforms like OpenStreetMap to assist in disaster relief and present first responders, humanitarian aid, and governments with the data needed to make informed decisions. Preemptive efforts have also been made to map the missing places of the world to increase the visibility of communities that have little to no base map available and are overlooked by governments and humanitarian aid. This has stemmed from ethical questions regarding the underrepresentation of the global South due to most humanitarian aid contributors residing in the global North on platforms such as OpenStreetMap. The recent integration of big data and artificial intelligence has shown great potential in the ability to process larger amounts of data at a faster rate. However, there are still ethical concerns and implications regarding the algorithms and modeling. This chapter covers the origins of humanitarian mapping, its progression over the last decade, the organizations at the forefront of innovation in the field, and the ethical implications that must be considered when shaping the directives of humanitarian mapping.

Tags

Introduction

Maramara, C. (2025). GIS&T and Humanitarian Mapping. The Geographic Information Science & Technology Body of Knowledge (2025 Edition). (2025 Edition), John P. Wilson (ed.). DOI: 10.2222/gistbok/2025.1.22.

Explanation

- Introduction

- OpenStreetMap

- Why Do People Contribute?

- Ethical Concerns

- Emerging Trends and the Future of Humanitarian Mapping

1. Introduction

1.1 Digital Humanitarianism and Humanitarian Mapping

Humanitarianism is taking action to improve the living conditions of others or assisting other human beings in a time of need. It is also widely held as an organized response to emergencies like wars and disasters. Humanitarian initiatives attract volunteers for ethical, religious, cultural, and humanist beliefs, as well as political agreements. Projects focus on local, national and international levels and address a wide breadth of needs. Humanitarian aid projects often require rapid and informed decision-making based on a reliable base of comprehensive and timely information. Current and accurate data on population, demographics, services, resources, road network status, weather conditions and topography are essential to informed decision-making. Oftentimes, the area of focus has data gaps and is out of date, which can mean first responders and governments unfamiliar with the area are forced to operate with an inaccurate base map. This usually occurs in less developed areas with no organized data infrastructure and can lead to ineffectual emergency response. On the ground, responders often create maps as necessity arises; a data deficit means decisions are made based on cost benefit analysis, advocacy, politics or educated guesswork, which can adversely affect the population in need. Humanitarian mapping is the production and use of spatial data and maps as part of a larger goal towards humanitarian information management. With the growth of geographic information systems (GIS) and digital mapping platforms, mapping has become synonymous with digital humanitarianism. This allows geographically distributed mappers to contribute their skills and coordinate with areas in need around the globe. The availability of GPS location on mobile phones has also increased the availability of highly accurate, real time, spatial data. Due to these technological innovations, humanitarian mapping has shifted from governmental experts and large humanitarian organization providers to nonprofessional, volunteer contributors and smaller humanitarian organizations as providers (Cinnamon 2020).

1.2 Evolution of Humanitarian Mapping

Humanitarian mapping is a dynamic and rapidly evolving field that has consistently leveraged advancements in technology, shifts in policy, and the efforts of passionate contributors. In the late 20th century, a pivotal moment came when President Bill Clinton ended Selective Availability on public GPS systems, allowing civilians access to much more accurate location data. This access to highly accurate geospatial data sparked innovation across both government and private sectors. Between 2003 and 2007, the U.S. government launched the first Humanitarian Information Unit, OpenStreetMap was founded, and both Google Maps and Google Earth were introduced—ushering in a new era of geospatial access and participation to the general public (American Geographical Society, 2020). These developments laid the groundwork for greater public engagement with mapping tools. The release of the iPhone further revolutionized the field by bringing these technologies together in a single, portable device. By 2009, the arrival of high-resolution satellite imagery and the rise of “crisis mappers” marked another leap forward. This momentum culminated in the humanitarian response to the 2010 Haiti earthquake, often referred to as the birthplace of modern humanitarian mapping. For the first time, volunteers could contribute remotely through crowdsourced platforms like OpenStreetMap, collaborating with aid workers on the ground to digitize satellite imagery and provide real-time support (Laituri, 2021).

Following the success of humanitarian mapping during early disaster response efforts, the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) expanded its mission. Major global institutions such as the World Bank and the United Nations began contributing data and resources, working alongside nonprofits that emerged to support the cause—such as Missing Maps, MapGive, and YouthMappers, all established by 2014 (American Geographical Society, 2020). The growing popularity and impact of these initiatives enabled a shift from purely reactive mapping—triggered by crises—to proactive mapping efforts aimed at preparedness and resilience in vulnerable areas. In recent years, the field has been further transformed by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI). Machine learning is now being used to generate geographic data and identify map features across platforms, accelerating the mapping process (Herfort et al. 2019). The management and application of big data and AI contributions to platforms like OpenStreetMap represent a continually evolving area, requiring both technological advancement and institutional collaboration. Despite these ongoing changes, the core mission of humanitarian mapping remains steadfast: to provide critical geospatial data in support of humanitarian relief and disaster response.

1.3 Information and Project Management

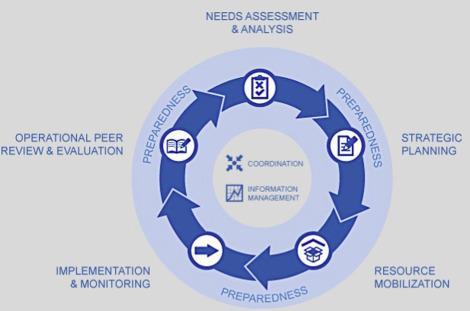

One of the most essential roles of GIS contributors is the acceleration of evidence-based decision-making. Maps, at their core, are the simplification of complex data. GIS can contribute throughout the many stages of humanitarian project cycles. Contributions can be made for prevention, data collection, and both rapid and long term data analysis. Data can come from community sources, emergency responders, social media, and remotely sensed images. The United Nations has a process for disaster management called the UN’s Inter-Agency Humanitarian Program Cycle (HPS) (shown in Figure 1) that demonstrates all stages of a humanitarian aid project. This highlights the role of GIS in various phases of humanitarian interventions, from initial needs assessment to strategy development and mobilization. At its core, humanitarian aid is deeply geographic at every stage, which is why GIS has been embraced by this community as an invaluable tool (Cinnamon 2020).

The structuring and analysis of data with visual outputs can make for powerful decision-making tools in the preliminary, implementation, monitoring and evaluation stages of a project. GIS can be used to determine ideal locations for outreach stations or medical care and coordinate resources in a disaster zone where conditions are constantly changing.

2. OpenStreetMap

2.1 Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT)

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is an open source and crowdsourced digital mapping platform that was created in 2004 by Steve Coast and made famous by its millions of contributors. The site has worldwide contributors that trace imagery from satellites, upload GPS location data and use a “wiki” contribution community editing model similar to Wikipedia. Their licensing model was previously Creative Commons and is now Open Data Commons. Participants are encouraged to share and use the data from OSM wherever applicable. The ability to edit OSM as long as the user has internet access makes the platform ideal for humanitarian mapping (Cinnamon 2020).

The Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) is an international team within OSM that is dedicated to humanitarian action and community development through open mapping. Their provided geospatial data has led the way in disaster management, and risk reduction; it works towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. They partner with relief agencies like the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders as well as governments and first responders (HOT: Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team). HOT provides thousands of online volunteers for disaster relief. It also contributes to the preemptive mapping of roads and buildings in less developed areas. These preemptive mapping contributions are done remotely using satellite imagery to add roads and buildings. These contributions are then verified by a secondary source. Finally, on the ground, mappers can add detailed information such as building types and road names (Cinnamon 2020).

2.2 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

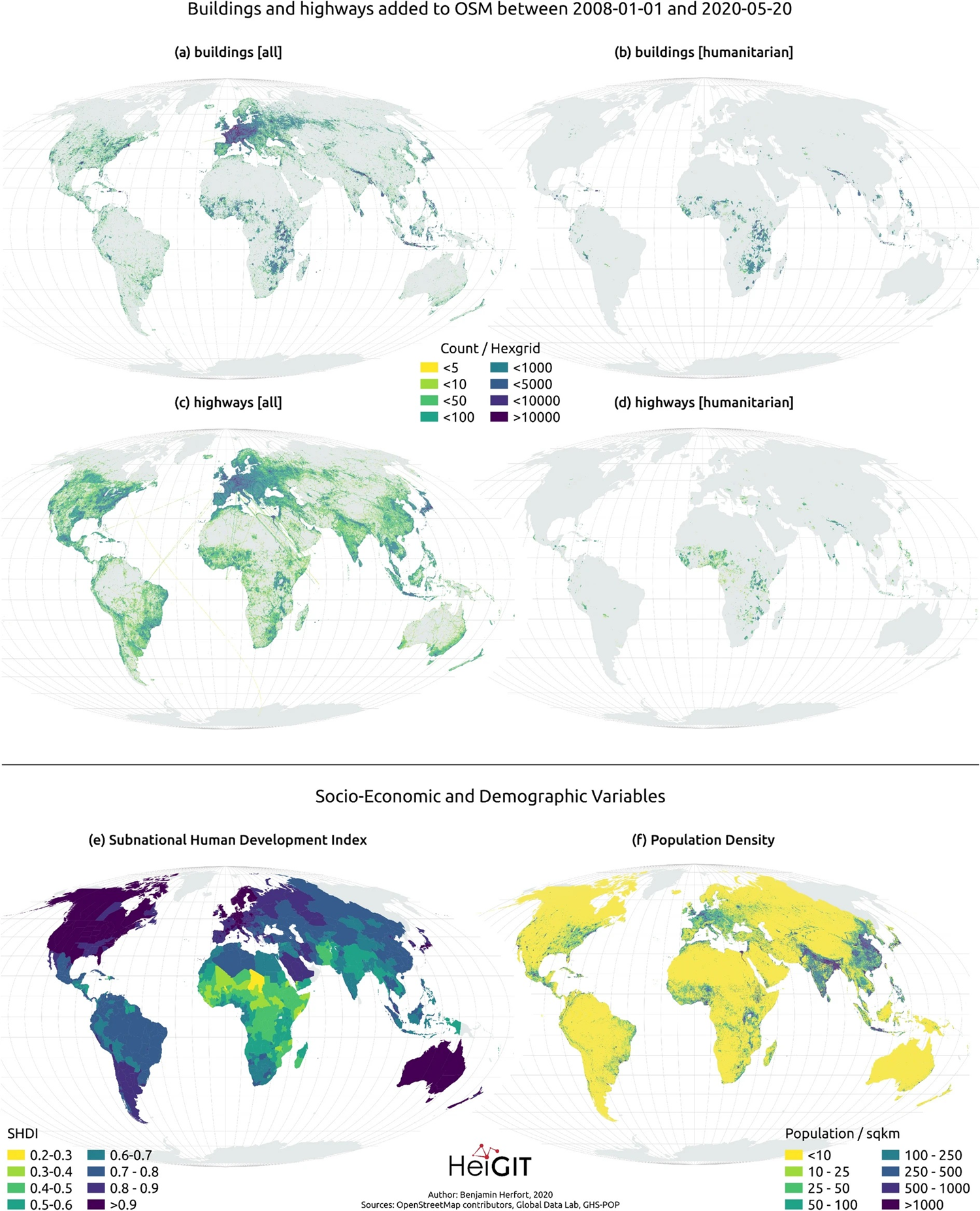

A priority of HOT’s impact statement is to make global scale contributions towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To monitor and evaluate this work, their evaluation framework is “constantly evolving to ensure tangible and measurable impact” (HOT: Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team). The overarching goal of the SDGs is to provide a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future (United Nations, n.d.). Many of the humanitarian mapping initiatives that OSM (HOT, Missing Maps) has undertaken have been in an effort to overcome the data gap that shows a strong bias towards Europe and North America due to many OSM contributors residing in the region as well as the higher development index, which is shown in Figure 2. This bias exacerbates the socio-economic inequities and digital divide that OSM has been trying to rectify since humanitarian mapping’s initial rise to prominence in 2010 (Herfort et al. 2021). Figure 2 shows all buildings and highways that have been added to OSM between 2008-2020 and a comparison map of only the humanitarian mapping contributions. In this figure, the bias of Europe and North America is clearly shown when compared to global population distribution and human development at the sub-national level.

The first SDG aims to eradicate extreme poverty for all people. Poverty is increasingly prevalent in urban areas where informal settlements are common. These settlements are often not recognized by governments and go unmapped even though they have no access to basic services and are most vulnerable to natural disasters, climate change and conflict. Mapping these settlements can be an important step for emergency services as well as official recognition by governments (Stampach et al. 2021).

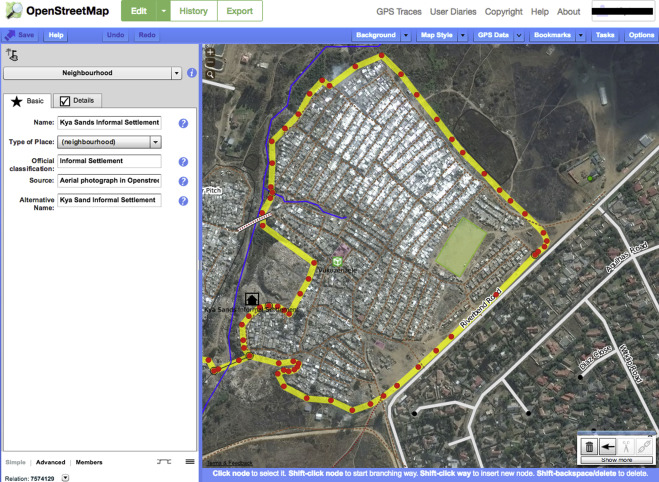

Figure 3 shows a mapping project undertaken by OSM of the informal settlement in Johannesburg, South Africa known as Kya Sands. Informal settlements are unauthorized and do not comply with authority requirements for formal townships. They are also often located on land that is not designated for residential use. This marginalized community is populated by 20,000 people and is at high risk for fires that destroy homes. Mapping this community can help with situation awareness and preparedness in a crisis (Cinnamon 2020).

The third SDG focuses on "ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being" (United Nations, n.d.). This goal, aimed at achieving global public health equity, became closely connected with humanitarian mapping during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa. The United Nations, in collaboration with the World Health Organization and GISCorps, launched its first emergency health mission to track the spread of Ebola, aiming to mitigate the impact of this global health crisis (GISCorps 2015). In response to the outbreak, innovative humanitarian mapping tools were developed, such as ArcGIS’s Survey123 (Koch, 2016). This tool enables users to collect and analyze data using custom forms that can be completed via the Survey123 app. Humanitarian mapping continues to play a crucial role today, especially during disease outbreaks, as decision-makers rely on up-to-date data that is regularly refreshed to respond effectively to emerging health threats.

2.3 Missing Maps, Mapathons, and YouthMappers

The Missing Maps project was started in 2014 with the goal to improve the availability of spatial data resources in an emergency and for longer term preventative projects. Currently, it is more focused on preemptively putting vulnerable places on the map in partnership with the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders (Stampach et al. 2021). Many places do not have an accurate and up-to-date base map. In worst case scenarios, these places are literally missing from open and accessible maps. This lack of visibility can create social inequity and confusion in an emergency situation when emergency responders need to navigate an area (Missing Maps). Urban management agencies often pay inadequate attention to the needs of areas that operate outside the formal planning process. Mapping can help ensure basic services get to these areas (Laituri 2021).

Mapathons are often organized by students and involve tracing satellite imagery for the OSM platform for targeted geographic areas. No expertise is needed and all contributed data goes through a secondary level of validation to ensure its accuracy (Stampach et al. 2021). These Mapathons contribute to the 147 million buildings and 2.7 million roads that have been added to OSM, according to the HOT website to date. YouthMappers has also been a successful program to promote youth leadership in countries and communities that need mapping (YouthMappers). Organizations such as Missing Maps, Doctors Without Borders, and TeenMaptivists simplify the process for individuals wanting to get involved by providing planning checklists, event day guides, and the option to register an event, making it easy for anyone to organize their own Mapathon events (Missing Maps).

2.4 The Ushahidi Platform

The Ushahidi Platform was developed to address the violence surrounding the 2008 Kenyan election and uses Google Maps API as well as OSM for its base map. The platform accepts contributions of thematic spatial data such as reports of damage, violence, or looting via mobile phones or the Internet. It also allows contributors to geotag multimedia digital content and social media and is used as a combination of social activism, citizen journalism and geographic data (Ushahidi). The platform is often used for crisis response, human rights reporting, and election monitoring.

The Standby Task Force is a crisis mapping network for the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) that makes interactive maps of natural disasters like Puerto Rico’s Hurricane Maria in 2017. The task force used the Ushahidi platform to assemble reports of damage from diverse online sources like media reports, social media posts, satellite imagery and FEMA data to create a comprehensive map with real time data for the Puerto Rican government (Cinnamon 2020).

3. Why Do People Contribute?

The latest shift of humanitarian mapping to volunteer contributors has shown a huge impact on the mapped world. In projects like Missing Maps and Mapathons, volunteers map a predefined location by remotely tracing satellite imagery to place buildings and roads on the map. This reliance on volunteers for mapping underdeveloped areas has stimulated research on why people contribute to humanitarian mapping. Many contributors self-evaluate their motivations as altruistic or dedication to the OSM Project and the mapping community (Stampach et al. 2021). Successful programs like YouthMappers showed a dedication to working towards specific SDGs; this motivated students to be socially responsible and feel more connected to the mapping community. The success of OSM and humanitarian mapping has been due to the community-building abilities of the OSM community. Social Mapathons promote a passion for humanitarian mapping by initiating new mappers into the practice, having them produce maps throughout the event, and retaining these newcomers for future events (Stampach et al. 2021).

4. Ethical Concerns

Nonprofessional involvement in humanitarian mapping allows more people to contribute, however there are some concerns about the accuracy of contributed data. Large numbers of nonprofessional contributors results in fast, low cost mapping power but can also cause a loss in quality and accuracy. Due to OSM’s longevity, time has shown that OSM generates a high degree of accuracy. This can be attributed to the community of mappers on the platform as well as the use of usernames to trace all contributions back to a source, if necessary (Haklay & Weber, 2008). HOT also uses other volunteers as a self-policing, second-stage data quality assurance system to ensure the accuracy of data. The spatiotemporal limitations of crisis management often outweigh the issue of data accuracy as well. In a crisis, ethical concerns about inaccurate data can be mitigated by the need for real-time data when entire communities are at stake. Sometimes, volunteer data is all that is available. It has been posited that the risk of false data is a loss of resources, but if that data was not available, lives could be lost altogether. If a community is in peril but there is no map of this community and no report of emergency, then the ethical choice would be to risk data inaccuracy in an effort to save human lives (Goodchild & Glennon 2010).

The use of big data in humanitarian mapping poses ethical concerns about privacy and surveillance. When private companies control users’ data, there are ethical concerns about who has access to it. This data is often restricted to most, but can be bought for a price. The socio economic restrictions on big data run opposed to the open source principles that OSM and humanitarian mapping align with. The increased use of Artificial Intelligence for humanitarian mapping is another ethical concern because of the automated process of tracing and extracting geographical features from remotely sensed images. AI can increase the speed of data acquisition, but automated processes can lead to “spatial sorting,”algorithmic bias, and reduction of importance of places (Cinnamon 2020). There is a clear bias in OSM mapped areas with most mapping in the Global North. These same contributors would be creating automation models, leading to a potentially biased foundation in AI algorithms (Hefort et al. 2021)

OSM and HOT consist of geographically-distributed volunteers that most often reside in the more developed nations of the Global North. These contributors do not live in the communities they are mapping. This outsourcing can disempower local participation and in turn disengage residents from gaining local knowledge and participating in decision-making for their own community. While remote tracing of satellite images is cheaper and faster, it should always be paired with on-the-ground data collection that involves local participation. Otherwise, Global North contributions for humanitarian mapping will reinforce an unbalanced global power structure (Herfort et al. 2021). These same people are choosing mapping locations, doing the mapping and structuring the programs, which could be seen as a reinforcement of colonial power structures. It is important within humanitarian mapping to collaborate with target communities and teach the skills needed for mapping contribution. This involvement will create a bottom-up program structure that starts with community input on the goals of the project in order to address residents’ real needs.

5. Emerging Trends and the Future of Humanitarian Mapping

The use of big data in humanitarian mapping has become more prevalent, leading to questions of the digital divide and private data company gatekeeping. Passive collection of geo-tagged Twitter data has been a strategy used to process large amounts of data in a short amount of time. The data can be analyzed to identify the clustering of tweets; these locations are used as proxies for identification of human active regions. Deep learning based models are then integrated to further map any missing built up areas (Li et al. 2020). The drawbacks to these data sources are the lack of contextualization, which can lead to bias and underrepresentation in some locations if there is no access to Twitter or the internet. These data collection methods can also only be used if the public is given access to private company’s social media data.

The introduction of artificial Intelligence (AI) and deep learning in humanitarian mapping has allowed for the automation of tracing geographic features from remotely sensed images. If integrated correctly, AI and deep learning can increase data quality, speed and diversify information types. The field has shown success with the integration of deep learning and crowdsourcing by delineating the stages best served by human skill and the stages best served by automated approaches. This lessens the reliance on human volunteers while still increasing output (Herfort et al. 2019).

The evolving OSM community has been significantly influenced by AI and the increasing involvement of corporate mappers, who contribute a large portion of the data to the platform. This shift has sparked debates about policies aimed at enforcing accountability for both nonprofit and private corporate mapping, with the goal of ensuring meaningful, transparent participation from large editing teams (Anderson et al., 2019). Concerns have risen within the OSM community regarding private companies like Mapbox, which employ teams of corporate mappers with private agendas often prioritizing road network mapping over buildings or points of interest. Critics argue that this undermines the principles of crowd-sourced wisdom and local knowledge on which OSM was founded (Anderson et al., 2019). Instances have been reported where corporate mappers have edited out local contributors' work, and challenges have emerged in scaling the validation process for such large corporate teams. Additionally, questions have been raised about the lack of data reciprocity, as private corporations have access to mapping data but do not share it with the OSM community.

These emerging issues reflect the ongoing evolution of humanitarian mapping since its origins during the Haiti earthquake. New tools have been developed, and various organizations have innovated to allow the public to engage in humanitarian mapping on a much larger scale than ever before. The integration of AI,

big data, and private corporations with traditional volunteer or nonprofit contributors presents both opportunities and challenges for the field. As the technology evolves, humanitarian mapping continues to expand its reach, helping more people than ever while navigating these complex issues.

References

- American Geographical Society. (2020, October 15). Mapping in Response to Humanitarian Disaster, presented by Joshua Campbell at AGS Fall Symposium, Geography [video].

- Anderson, J., Sarkar, D., & Palen, L. (2019). Corporate Editors in the Evolving Landscape of OpenStreetMap. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 8(5), 232.

- Cinnamon, J. (2020). Humanitarian Mapping. In A. L. Kobayashi (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second edition.), 121-128. Elsevier.

- GISCorps. (2015, May 3). GISCorps Assists World Health Organization in Mapping Ebola Response Activities. Ebola missions with WHO.

- Goodchild, M. F., & Glennon, J. A. (2010). Crowdsourcing geographic information for disaster response: a research frontier. International Journal of Digital Earth, 3(3), 231–241.

- Haklay, M. & Weber, P. (2008). OpenStreetMap: User-Generated Street Maps. IEEE Pervasive Computing, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 12-18.

- Herfort, B., Lautenbach, S., Porto de Albuquerque, J., Anderson, J., & Zipf, A. (2021). The evolution of humanitarian mapping within the OpenStreetMap Community. Scientific Reports, 11(1).

- Herfort, B., Li, H., Fendrich, S., Lautenbach, S., & Zipf, A. (2019). Mapping Human Settlements with Higher Accuracy and Less Volunteer Efforts by Combining Crowdsourcing and Deep Learning. Remote Sensing, 11(15), 1799.

- Koch, T. (2016). Fighting disease, like fighting fires: The lessons ebola teaches. Canadian Geographies / Géographies Canadiennes, 60(3), 288–299.

- Laituri, M. (2021). Mapping Spatial Justice for Marginal Societies. The Geographic Information Science & Technology Body of Knowledge (1st Quarter 2021 Edition), John P. Wilson (Ed.).

- Li, H., Herfort, B., Huang, W., Zia, M., & Zipf, A. (2020). Exploration of openstreetmap missing built-up areas using Twitter hierarchical clustering and deep learning in Mozambique. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 166, 41–51.

- Štampach, R., Herman, L., Trojan, J., Tajovská, K., & Řezník, T. (2021). Humanitarian Mapping as a Contribution to Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: Research into the Motivation of Volunteers and the Ideal Setting of Mapathons. Sustainability, 13(24), 13991.

Learning outcomes

-

1896 - What are the leading methodologies in humanitarian mapping? How have they changed over time? What are the new directions they are going in?

What are the leading methodologies in humanitarian mapping? How have they changed over time? What are the new directions they are going in?

-

1897 - How are the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals influencing the objectives of humanitarian mapping and are they being met?

How are the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals influencing the objectives of humanitarian mapping and are they being met?

-

1898 - What are the ethical concerns that need to be taken into account in the field of humanitarian mapping?

What are the ethical concerns that need to be taken into account in the field of humanitarian mapping?